A Jewish Family in Malta

A Jewish Family in Malta

First published on adriangrima.com

An interpreter by profession, Aline P’nina Tayar is a descendant of the famous Jewish business family Tayar – many will remember their shop where Marks and Spencers now stands in Valletta- who lived and thrived in Malta for over a century. She has written a fascinating book, full of telling anecdotes, tracing her extended family’s lives in Malta, and around the Mediterranean. The book also provides a compassionate, wry insight into social mores on the island, especially regarding Maltese and Jewish relations. She gave a talk in Malta recently and answered some questions Gillian Bartolo put to her.

Why did you write this book?

I began writing How Shall We Sing? A Mediterranean Journey Through a Jewish Family (Australia: Pan Macmillan/Picador, 2000) in my mid-40s, when I was going through a difficult time (partly the result of the deaths of a number of friends) which suddenly created a crisis of identity in me. Like most people from large families, I had a vast store of family stories and anecdotes and it seemed to me that the time had come to put them down in writing. At first that appeared to be sufficient, but then it very gradually became obvious that if I was going to publish these stories I needed to give them a structure. After countless drafts and re-drafts, I found that the structure would come from the theme of identity – both my own identity and the identity of the different branches of my family within the different Mediterranean communities they lived in. As someone who had lived in so many places, I felt that at that particular juncture in my life (with all the terrible losses) I needed a sense of belonging and since I could not/cannot say that I belong wholly to any specific nation nor do I have religion to fall back on (I was brought up without any religion at all though I was always aware that I was a Jew culturally), finding my place within my vast and far-flung family emerged as the theme of the series of stories told in How Shall we Sing?

Can you give me a brief history of your family in Malta?

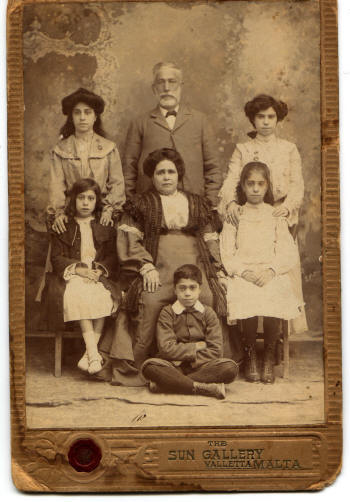

My great great grandfather Rabbi Josef Tajar (later generations changed the spelling to Tayar) came to Malta in 1846 from Tripolitania. The Jewish community having grown large enough (to about 100 people) to support a rabbi part-time, Josef set up a congregation on what was then known as the Strada Reale. ( Expelled from Malta and Gozo by Spanish in 1492, Jews had not been allowed to establish residence in Malta throughout the 350 years the Knights ruled the islands. When Napoleon expelled the Knights and more especially after the British took over, Jews started to settle in Malta again.) The Jews were allowed to practice their religion though from time to time they did feel under threat – the fact that there were many poor Jews arriving on the island, particularly after the 1848 revolutions all over Europe, made the local authorities nervous and when they called for a census to be taken the Jews became afraid that the purpose was to eventually drive them all out. In the 1890s the Blood Libel against the Jewish community led them to appeal for protection from London, but on the whole ordinary Maltese were not unkind, mostly (in my opinion at least) because they didn’t really know what Jews were – the story of mm grandmother’s’ neighbours bringing the statue of Mary to her house when she was dying is an example of how even in modern times the Maltese didn’t quite know what the Jews did or did not believe in. (My aunts were horrified and sent the kind women away.)

My great great grandfather Rabbi Josef Tajar (later generations changed the spelling to Tayar) came to Malta in 1846 from Tripolitania. The Jewish community having grown large enough (to about 100 people) to support a rabbi part-time, Josef set up a congregation on what was then known as the Strada Reale. ( Expelled from Malta and Gozo by Spanish in 1492, Jews had not been allowed to establish residence in Malta throughout the 350 years the Knights ruled the islands. When Napoleon expelled the Knights and more especially after the British took over, Jews started to settle in Malta again.) The Jews were allowed to practice their religion though from time to time they did feel under threat – the fact that there were many poor Jews arriving on the island, particularly after the 1848 revolutions all over Europe, made the local authorities nervous and when they called for a census to be taken the Jews became afraid that the purpose was to eventually drive them all out. In the 1890s the Blood Libel against the Jewish community led them to appeal for protection from London, but on the whole ordinary Maltese were not unkind, mostly (in my opinion at least) because they didn’t really know what Jews were – the story of mm grandmother’s’ neighbours bringing the statue of Mary to her house when she was dying is an example of how even in modern times the Maltese didn’t quite know what the Jews did or did not believe in. (My aunts were horrified and sent the kind women away.)

Relations with the Church however were not so easy. I recount in How Shall We Sing? how when my uncle Oscar announced he was going to marry a Catholic girl, the poor young woman was summoned to the Bishop’s Palace in Valletta and subjected to a real inquisition. At the same time, my grandmother Rachele, in a state of shock that my uncle was planning to ‘marry out’, took to her bed for a whole year.

My grandmother’s father, Jacob Israel, arrived in Malta in the 1860s from Corfu. His wife Giulia was from Sfax in Tunisia from where she’d arrived in Malta with her widowed father, a rabbi, following a famine in the south of the country.

And the next generation?

Rabbi Josef Tayar’s children were mostly businessmen and settled all round the Mediterranean. My great grandfather Cesare opened a shop on Palace Square which my grandfather Abraham (Banino) inherited and in which he set up his tailoring business (my aunts Ondina and Margot kept the shop running after he died and went on selling fine cloths for suits until the shop was bought up by Marks & Spencers). Irene, Banino’s sister, was the mother of George Tayar and married to Achille Tayar, a first cousin (allowed in Judaism and certainly not unusual in a small Jewish community which didn’t look for husbands or wives outside their religion). Achille was a very successful merchant, with an impeccable reputation for honesty. Of that generation, one cousin was British Consul in The Yemen.

Of my father’s generation, George was a well-know businessman and philanthropist (a street in Kappara is named after him as a result of the latter). He was always happy go lucky and is still remembered for the permanently open house he kept – and also for his support of Labour. My uncle Oscar was the first Jewish civil servant on the island. Ondina, one of my father’s five sisters, was one of the first women to graduate (in Pharmacy) from University of Malta. Margot was also a civil servant. Three sisters, Yolanda, Doris/Juliette and Lilla (also a Pharmacy graduate) left the island when they married and ended up respectively in Tunis, Argentina then Canada, and Florence. My father, Duggie was an officer/interpreter in the 10th Baluch Regiment, a part of the Eighth Army during WWII. On his return from India in 1947, he became a Customs Officer. He married my mother, Lina Lumbroso, in Tunisia in September 1947.

What sort of political allegiances did they have?

In the 1930s – my father’s family were very pro-British in spite of the fact that they spoke Italian at home, a legacy of my grandfather Banino’s mother Corinna Coen who came to the island from Florence when she married Cesare (see above). When Mussolini attacked Abyssinia, they ceased speaking Italian at home and switched to Maltese. Ondina (whose published short stories I only have a photocopied couple of) switched from writing in Italian to writing in Maltese. In my book I recount an anecdote of my father being ordered to change his name from Douglas to Alberto by his pro-Italian headmaster. Professor Victor Griffiths told me only last Saturday that the same thing happened to him. His father and my grandfather both protested to the British Governor and both boys had their proper names re-instated.

Achille, George’s father, on the other hand, remained pro-Italian for quite some time, until he saw what the Fascists were doing to the Jews in Italy, but that was already quite late into Mussolini’s ‘reign’.

What was your family’s opinion of the Maltese?

Although my family always spoke of the Maltese as ‘they’, it was more of a habit than anything else. My aunt Ondina was a fellow student of Censu Tabone’s and remained friends with his family ever after – she always told us how poor Censu had been and how she often gave him some of her sandwiches and Censu recently told me that the brass plaque which is still on his door in St. Julian’s and which reads V. Tabone M.D. was actually made by Ondina – he was too poor to have one made professionally. Margot was a good friend to Maria Tabone, helping her with her many children during all of Censu’s long absences from the island when he worked for the WHO.

The above sounds a bit like name-dropping – sorry! There were many other Maltese friends, but when Ondina fell in love with a Catholic, religion emerged again as the thing that ultimately divided the Tayars from the people around them. She did not have the courage, like my uncle Oscar, to cross the religious battle lines and marry, something she always regretted, even up to the last weeks of her life(she was 91 when she died and still repeating how regretful she was).

Why did your family emigrate to Israel when you were 18 months old, and why did they leave for Australia a few years later?

My family emigrated to Israel because my father, as a socialist and idealist, wanted to live in a commune, which is basically what a kibbutz is, a society without money and minus the usual (he thought) keeping up with the Jones’s. My mother too was keen to settle in Israel to get away from the small and stifling communities she’d lived in first in La Goulette/Tunis and then, upon her marriage, in Malta. What they discovered is that there’s no more stifling a hothouse than a kibbutz. Our kibbutz was also a particularly left-wing one – to the extent that alongside the Hatikvah, they played The Internationale at kibbutz meetings, something my parents did not agree with especially in the light of revelations about what had happened in Russia under Stalin. They also didn’t like the hierarchy that existed between older and new members in the kibbutz. The deep division between Ashkenaz (Jews of central and eastern Europe and their descendants) and Sephardic Jews (Jews of Spain and Portugal and their descendants) within the kibbutz soon led to their complete disillusionment with the whole kibbutz ideal, which they felt had been corrupted. When my father broke his back and was no longer able to do hard physical labour my parents decided to leave Israel.

The move to Australia was purely because the Australian government was offering an assisted passage. My parents had also applied to go to NZ and Canada and the US. Anywhere, to get out of the kibbutz!

Why did you come back to Europe?

I came back to Europe as part of that great exodus of Australian youth in the 1960s and 70s – Australia seemed so far away and so isolated culturally and many of us wanted to experience something different. As a language graduate, I also wanted to try living in France and Italy. Nothing to do with my roots at all – in fact when I first arrived and went to live with my mother’s brother in Paris I found that Tunisian Jewish Diaspora totally alienating.

My parents thought that by going to Australia they could remove us from all the divisions they’d experienced in the places they’d grown up in and, disappointingly, also in Israel. We had no connection with any ethnic community in Sydney – neither the Maltese, nor the Italian and especially not the Jewish community which mostly congregated on the other side of the harbour anyway. Besides which they were principally Ashkenaz and we were Sephardic so our customs, food, tastes were very very different. At school, it was hard to be an outsider however – my father did not want us to attend religious instruction (for which, by the way, these days I’m eternally grateful!) and this made my brother and me oddities. Kids, as you know, are conformists. My brother hated this non-conformity and even I at first found it hard – one should remember that Australia in the 1950s still required people looking for jobs to state their religion (and when my father refused to state his religion but put down that he was born in Malta people automatically assumed he was Catholic and denied him work – what irony!). The odd thing was that at school I often gravitated towards Jewish people – though in primary school there were only two Jewish girls in my class, in high school there were about a dozen. At university, my best friend was a Polish Jewish student who like me had grown up suffering from the confusions of 20th century history – speaking Polish, the language of the people who’d driven her parents out of Poland after WWII, and also with no religious belief.

Many non-Jews think that all Jews are by definition religious. But this is obviously not the case.

This lack of religious belief probably seems strange to you as it does to many Christians – how can you call yourself a Jew when you don’t believe in God? The answer was given by Rabbi Hillel, of whom Jesus was a follower. Rabbi Hillel was once asked to stand on one leg and recount allJewish beliefs in one go. Which was a cinch since it took him no time to encapsulate what Judaism was about. ‘Do not do unto others what you do not wish them to do to you’ he said. No mention of God. This is the central precept and no more is needed, not even a belief in God. Jesus, by the way, took the precept and turned into something slightly different ‘Do untoothers what you would wish to be done to you.’

That precept is precisely what my parents tried to instill in both my brother and me rather than a belief in an all-powerful deity.

Have you discovered your identity at last?

At the end of my search for who I am and what I am, I have discovered that rather than seeing my multiplicity of origins as a burden,I can use them to my advantage. I can be whatever I want to be and have an ‘in’ into a huge variety of cultures and ways of living. I am both an outsider in the places I have lived in and an insider because I have lived in them.

For some time, you have visited Malta every year. Do you feel a strong connection with the island?

Now that only my uncle Oscar is left on the island, I feel that my connections with the island are disappearing. I have in the last two years been trying to learn Maltese, not for work, but just to keep the connection with the island going – as a linguist by profession, learning Maltese seemed a logical step. If only someone would organise a course for foreigners in Maltese, I’d be back like a shot!

This last visit to Malta was very sad for me, having to draw up an inventory of my aunts’ belongings in their old house in St. Julian’s and living for several days with their ghosts and the ghosts of all the people who’d lived in or passed through the house which I have always loved in spite of its rundown condition over many many years – it became too difficult for my ageing aunts to keep it in good order. I’d be very sorry if the property developers were to carry out their usual depredations and pull the place down to build some more ugly apartment buildings.